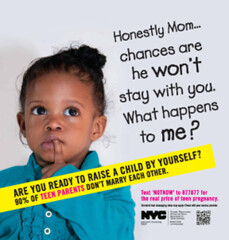

Poster for New York City’s “Real Cost of Teen Pregnancy” campaign. Via NYC.gov

By Guest Contributor Sayantani DasGupta

This month, New York City launched a new campaign called “The True Cost of Teen Pregnancy.” The 4,000 bus and subway posters, which reportedly took two years of planning and cost the city $400,000, feature wailing toddlers and babies (mostly of color) next to captions such as Honestly, Mom, chances are he won’t stay with you… and I’m twice as likely not to graduate high school because you had me as a teen.

Yes, teen pregnancy is experienced disproportionately by girls of color and girls living in poverty. Yet data shows that national teen pregnancy rates across ethnicities are dropping not rising, including in New York City. So why this public health campaign? And why now?

The race and class politics behind the “True Cost” campaign become more obvious when one considers that over the past years, the city has released several public health campaigns that have been critiqued as specifically targeting working class and poor communities of color. Indeed, public health campaigns are never value neutral, and are often used to orient social hostility toward marginalized groups.

While “True Cost” was quickly criticized, most of the pushback has focused on the problems surrounding the use of shame as a health promotion tool, not explicitly around its race and class message. For instance, the New York City Coalition for Reproductive Justice launched a ‘No Stigma! No Shame!’ campaign in response to the ad, and Planned Parenthood of New York City released a statement denouncing the posters, saying they perpetuated “gender stereotypes, stigmatizing and fear based messages” while ignoring the ‘structural realities’ impacting these young women’s lives (Code for racism and classism? Perhaps).

Then there is Richard V. Reeves, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institute, who defended the use of stigmatization and fear as motivations for healthy behavior in a column for the New York Times, arguing that “shame is an essential ingredient of a healthy society.”

Then there is Richard V. Reeves, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institute, who defended the use of stigmatization and fear as motivations for healthy behavior in a column for the New York Times, arguing that “shame is an essential ingredient of a healthy society.”

But Reeves’ voice has seemingly been an outlier. Even TED talk ‘shame and vulnerability’ rockstar Brené Brown has gotten into the conversation, arguing against Reeves’ conclusions by asserting, “Shame diminishes our capacity for empathy. Shame corrodes the very part of us that believes we are capable of change.”

But I don’t think the issue is purely about shame. The question is: who is being shamed and for what purpose? It is not a coincidence that New York’s current campaign shares a lot in common with a Georgia hospital’s 2011-2012 campaign against childhood obesity. Like the “True Cost” ads, these black and white photos of morose looking children were accompanied by fear-filled captions like WARNING: Chubby kids may not outlive their parents and WARNING: It’s hard to be a little girl if you’re not.

Both campaigns use children (the universal “innocent victims”) to blame parents – a strategy seen often in international development projects, such as Invisible Children’s problematic KONY 2012 campaign. In these narratives, entire communities, or countries, are portrayed as incapable of, or uninterested in, protecting and caring for their own children, or themselves. (Which then justifies everything from domestic governmental regulation to international interference in, or invasion of, other countries)

Consider that just last year, New York launched the “Cut Your Portions, Cut Your Risk” campaign. The most criticized ad of the campaign featured a slumped over, disabled African American man sitting on a stool, a pair of crutches resting near him. Below him are three cups of soda, each increasing in size. The slogan reads, Portions have grown, so has Type 2 diabetes, which can lead to amputations.

Yet as the Times reported, the image in “Cut Your Portions” isn’t real: the man’s leg was in fact photoshopped out of the image to suggest he was an amputee. Like the other ads of this series, the man’s face is also cropped out of the photo. By essentially making him faceless (and voiceless), the ad suggests that this man’s size, race, or perhaps his (artificial) disability, is so shameful it requires anonymity.

Posters from Georgia campaign against teen obesity. Via Freerangecomm.com

As a result, the viewer is able to gaze voyeuristically upon a disabled body of color and size without the risk of being implicated in the act of gazing, or having that gaze in any way returned. Like teenage mothers, who are made effectively invisible by the “Real Cost of Teen Pregnancy” ads, the African American man in the “Cut Your Portions” ad is marginalized from the cultural conversation.

Both these anti-teen-pregnancy and anti-obesity campaigns target teens and adults, who are likely working class or living in poverty, who are likely from Latino and African American communities. Both phenomena have been framed in the language of contagion: as ‘epidemics,’ a practice that dates back to the last century, when public health campaigns pushed their messages by reflecting socio-cultural anxieties about “unruly bodies.”

The archetypal figure in this kind of campaign was New York City cook Mary Mallon, who came to be known as “Typhoid Mary,” the asymptomatic carrier of the infection who came to embody the threat of the deadly outbreak in the early 1900s. The demonization of this one working class woman is the quintessential example of how oppression can be medicalized; in this case, how threat of disease contagion became conflated with social anxieties about the encroaching working classes.

World War II-era venereal disease (VD) campaigns often directly associated contagion with women’s bodies, and particularly, social anxieties about unfettered female sexuality. One such poster was an image of a giant, benignly smiling woman’s head floating above a group of male soldiers and civilians. The caption reads, She May Look Clean But… and You Can’t Beat the Axis if you get VD. Here, the female body is directly implicated in the breakdown of not only individual men’s health, but the health of the national body.

French poster: ” Tuberculosis, a great plague.” Via ww1propaganda.com

Similarly, tubercuosis (TB) campaigns of the past often directly associated the specter of death (personified by the Grim Reaper or a skeleton) with poor, immigrant, urban communities. Disease contagion became associated with social contagion, and the perceived threat to the social order embodied by immigrants and the poor. These campaigns taught the public not only about syphilis or tuberculosis, but how to think about the individuals associated with these medical threats.

The modern ‘epidemics’ of teen pregnancy and obesity can be understood as a modern manifestation of these sorts of anxieties about the ‘contagion’ of working class and poor communities, about “unregulated” female sexuality. Many sociologists have used the idea of “moral panic” to describe how society’s wider anxieties (about criminals, communities of color, the poor, immigrants, etc.) are framed as threatening to the social order, and transformed into hostility and volatility.

I don’t mean to imply that teen pregnancy is necessarily good for young women, or that there aren’t health outcomes of obesity (although the data has been surprising – with a recent analysis suggesting that being overweight might be actually associated with a lower risk of death). What I would like to argue is that since these “epidemics” – and these campaigns – disproportionately break down across class and race lines, these ‘shame and blame’ posters in fact serve to throw a cloak of moral legitimacy upon race and class panic.

The panic here is clear: marginalized bodies are out of control, unable to care for themselves or their children. Self-control (regarding sexuality, regarding food), so valued a Puritanical American ideal, is disintegrating, and a disintegration of the social fabric is sure to follow.

Public health campaigns which rely on shame rather than empowerment, which cast individual blame rather than crafting collective solutions, which target marginalized bodies rather than corporate entities like the food production and distribution industry, can be seen as symptoms of wider social ills: racist and classist public control disguised as public health.

Although these campaigns would have us believe that they are promoting the health of teen girls or fat adults (and I use the world here in solidarity with the fat activism movement), what they are really promoting is their social stigmatization. In New York City, ‘shame and blame’ health campaigns have become a moralizing weapon, promoting, not health, but social injustice.